[Editor’s Note: The following remarks were made by Peter Goldberger at a National Lawyers Guild war tax resistance workshop over Zoom on April 4, 2024. Goldberger addresses three subjects: the legality and ethics of counseling illegal activity; the particular risks faced by legal professionals contemplating participating personally in tax resistance; and the argument by certain activists that it is legal to refuse to pay one’s federal income taxes based on international law, since some of these taxes are being used to support genocide in Gaza. The subheadings were added by the editor.]

Providing Advice on Illegal Activity

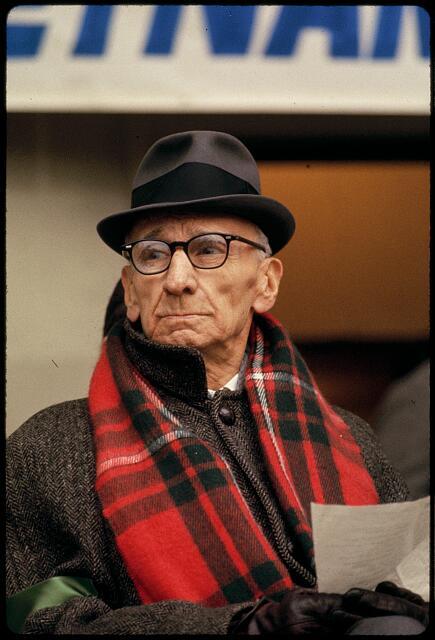

Peter Goldberger Speaking at NWTRCC Conference at Earlham School of Religion in November 2014. Photo by Ruth Benn.

I assume most of the people in the audience today, as at any Guild event, are themselves lawyers. And I’m sure we also have law students and legal workers participating. Some of you may be interested in providing counseling and support to others who are moved to consider tax resistance, even if you do not plan to participate in it directly yourself. There was some concern expressed in the discussions leading up to today’s event about whether there’s some ethical restriction on giving advice to people who are talking about engaging in civil disobedience or other illegal activity. I want to say very clearly that if done professionally, counseling with respect to planned illegal activity is not an ethical concern. In fact, that has been a significant part of my own practice for the last forty years, and I don’t think anyone has suggested that my practice is other than entirely ethical.

To “counsel” is not to recommend or encourage. I always say, “As a lawyer, I suggest that you do not break the law.” “As a lawyer, I also recommend, if you are deeply moved to break the law for some reason, that you do it with your eyes open and with full and accurate awareness of the consequences that may befall you, as well as of the benefits that it may bring to you in terms of your conscience and your self-esteem.”

Many people have engaged in civil disobedience and direct action of various kinds knowing full well that it’s illegal. This includes quite a few lawyers, who participated because they’ve balanced the benefits that they perceive to come to them from doing what they believe to be the right thing against the risks and consequences of engaging in illegal action. Helping people to make those decisions, as long as you don’t aid and abet the commission of a crime by recommending it or suggesting a way of carrying it out, or rendering material assistance to the criminal action, is entirely proper within the realm of legal counseling.

Even in ordinary legal practice, clients often want to know where the line is between legal and illegal activity. You have to be able to talk with people about what they are thinking about. If you can identify the line between legal and illegal conduct, you may think it’s prudent to recommend that people not go up to and put their toe right on that line in one context or another. But people may want to go right up to the line, and they’re legally entitled to go right up to the line. So they have to know where the line is. That’s what it means for the law to draw a line, as Oliver Wendell Holmes once said. And so telling people about risk is a perfectly valid form of legal counseling.

Increased Risk for Lawyers Engaging in Illegal Activity

Now, let’s talk about lawyers who may choose to engage in non-payment of tax. First, I think we all probably know that failure to pay all the tax that is due under the law is actually a very common circumstance, including among lawyers, usually not for good reasons, but just for selfish or careless reasons. And of course, very few get in trouble, maybe with the IRS, rarely with the Bar, and almost never are they prosecuted. But as Lincoln Rice mentioned a few minutes ago, the chances of being prosecuted for doing any given thing if you are a lawyer is higher than doing that same thing if you are not a lawyer. And I think that’s true of other professionals as well. I mean the ratio of accountants and lawyers who don’t pay their taxes and wind up being prosecuted is higher than of other professions, and much higher than the risk faced by the average person.

Civil Disobedience as a Part of the American Law Protest Tradition & the Legality of Refusing to Pay for War

A Tax Court ruled that the Nuremberg Principles did not justify A. J. Muste’s tax refusal. A. J. Muste speaking in Central Park in the 1960s. Photo by Bernard Gotfryd, located at Library of Congress.

There is a tradition in American history of people being motivated to resist taxes on account of their opposition to all war or to particular wars going back at least to the Revolution. This is a respected, honored piece of American law reform protest tradition in the category of civil disobedience. It’s not a new phenomenon. Probably the best known early instance is the opposition to the Mexican War in the 1840s by Thoreau and the other transcendentalists. Peace movement scholars say the high point of US anti-war tax resistance was the refusal by many thousands of people to pay what was then an excise tax on long-distance phone calls, which Congress had enacted explicitly to raise more money to pay for the American War in Vietnam.

And because it’s not new, some of the legal or legalistic arguments that Suad Abdel Aziz mentioned at the beginning of today’s program are also not new.

Most important, I want to be sure that you know that in 1961 the Tax Court held that avoiding complicity as a war criminal under the Nuremberg Principles did not justify A. J. Muste, the founder of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, and one of the great nonviolent activists of the ’50s and ’60s, in refusing to pay his income tax over the development and testing of nuclear weapons.

The same argument was made many times in the 1970s over the Vietnam War. There were certainly good arguments that the Vietnam War was unconstitutional, that war crimes were being committed in the use of the weapons against civilian populations, causing widespread civilian deaths in Vietnam. Many people claimed at that time that they had a privilege or a right under international law, even a duty, to avoid complicity that included refusing to pay taxes, at least half of which were going to support and carry on that war. But those arguments were considered, and absolutely universally rejected, in every court decision in which they’ve come up. The matter is considered settled to the point that financial penalties for frivolous litigation are commonly imposed by the Tax Court on those who try to advance the argument now, and making that argument in submissions to the IRS to justify an understatement of income or of tax due can likewise result in a frivolous filing penalty.

I’m not saying that the argument is not theoretically correct or that a person might not rely on it. But I think I have a responsibility, because I know this to be true, to say that these precedents still exist and are unlikely to be reconsidered. No one contemplating tax resistance as a protest against war crimes should expect to be vindicated in court, even if they may be vindicated in the judgment of history.

[Editor’s Note: Peter Goldberger is an attorney in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, and the longtime legal consultant to NWTRCC.

February 2, 2025

Is there a case for protesting federal taxes since we have an un-elected/un-appointed oligarch now in control of the Treasury parment system, as well as access to personal data with the DOGE cyber-attack on the country?