A common argument against war tax resistance goes something like this:

War tax resistance is counterproductive: The government will add penalties and interest to whatever you refuse to pay, and when they eventually wring the money out of you, in the end you’ll have given even more financial support to the military than you would have if you’d just paid up in the first place.

Today I’ll show you some evidence that I hope will convince you that this is not a very good argument.

Lots of people don’t pay the IRS what the agency thinks they should. The IRS has tried to figure out where this missing money is hiding, but their methodology isn’t all that great, and it’s not an easy mystery to solve.

Their best guess is that the vast majority of missing taxes comes from “underreporting” — that is, taxable activities that the IRS never becomes aware of. For example: if you placed a bet with a friend on the outcome of the Super Bowl, the winner of that bet should have added the amount won to their income and should have paid taxes on it, according to the IRS anyway. Most people don’t go out of their way to report taxable transactions like these that the IRS wouldn’t learn about on its own, and so a lot of these transactions never get taxed and they stay in the “underground economy.”

An estimated 84% of the “tax gap” comes from unreported taxable activities like these. Another 6% comes from taxable activities the IRS does learn about, but for which the responsible party never bothers to file a tax return. The remaining 10% comes from people whose tax debt is registered on paper according to Hoyle, but who never get around to forking over the money.

According to IRS financial statements for fiscal year 2014, there were at that time about $380 billion in outstanding unpaid taxes that it knew about. This includes about $205 billion in interest & penalties added to the originally-due taxes, but it does not count any taxes that people have thus far successfully evaded by keeping out of the IRS’s view — that is, all the stuff in the 84% blue area above, a category that some war tax resisters fall into. It also doesn’t include amounts that the agency can no longer pursue because the statute of limitations has expired, which also includes amounts resisted by some fortunate war tax resisters.

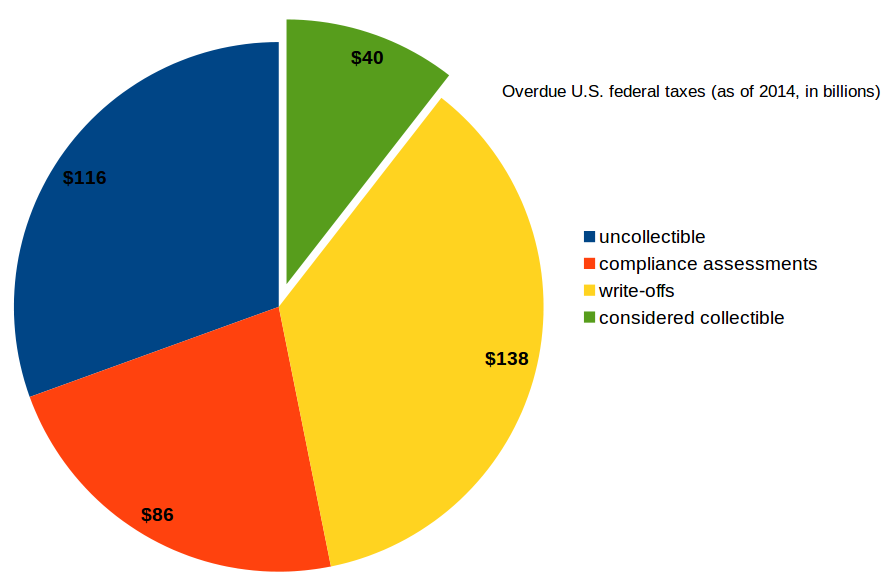

Of that $380 billion, the agency considers $116 billion to be “currently uncollectible” (“primarily because of the economic situations of the taxpayers”). Another $86 billion is something called “compliance assessments” — when the IRS tells a taxpayer who hasn’t filed a return (or a fully-revealing one) what the agency suspects the taxpayer would have owed if they had filed accurately, but the taxpayer isn’t going along with it and the controversy is still in limbo. The agency doesn’t have much confidence in collecting this money either. There is also a large category called “write-offs” that totals $138 billion. This is tax debt that is hopelessly uncollectible because the taxpayer is bankrupt, insolvent, dead, vanished into thin air, or something of that sort. That only leaves about ten percent of the total that the IRS considers to be collectible and includes as a potential asset on its financial statements.

To sum up: to $175 billion in unpaid taxes (that the IRS knows about), it has added $205 billion in interest & penalties, but it is only confident of collecting $40 billion of that total (in recent years it has actually collected closer to $46–49 billion per year by means of its enforcement arm, so it may somewhat exceed its expectations). This I think shows conclusively that people who refuse pay their taxes do not, in the aggregate, ironically end up paying more.

For war tax resisters — who are typically alive, solvent, and often have seizable assets and income streams — the news isn’t quite as good as this chart would suggest. But even from juicy targets like us, the IRS fails to seize enough money in penalties and interest from some of us to make up for the money it fails to seize from those of us it lets slip through its clutches.

For each war tax resister who is unfortunate enough to pay more than her or his share, there are others whose resistance is never successfully thwarted by the government, and when you consider them together they certainly cost the government and thereby deplete the resources available to it for military spending. An informal survey of war tax resisters a few years back, for example, found that the IRS had successfully seized only about 25% of what those resisters had refused to pay.

In addition, it is costly for the agency to deploy its collection apparatus: sending out all of those letters, filing liens & levies, managing the associated bureaucracy — all of that costs money. The IRS spends about five billion dollars per year on enforcement (including investigations, audits, and collection), and resisters contribute to this additional cost of the government conscripting our support for the military and thereby make this conscription less efficient.

So if you are hesitating to refuse to pay war taxes because you worry that by doing so you may inadvertently swell government coffers… I hope this has reassured you that in the aggregate, tax resisters do indeed deprive the government of funds.

Post by David Gross

As always, I’m grateful for David’s learned and thoughtful comments; I’m glad someone took up this question, and I’m glad it was David in particular!

For what it’s worth, though, as a long-time and multiply levied resister, I’d add that the question for me isn’t entirely relevant, though it’s certainly interesting. I regularly tell people that my way of doing war tax resistance is a lousy way of keeping money out of the hands of the of the government – true as far as it goes, as it concerns me as an individual, since I personally would have paid less had I not resisted than I’ve paid as a result of resisting. WTR for me is a mode of witnessing (and also what Randy Kehler has sometimes called a spiritual exercise). Some people call this a “merely” symbolic act; it is indeed symbolic, but symbols are important too, so I’d dissent from “merely.”

this past week-end in San Diego was a whirlwind of progressive events, around BLM, community gardening, slavery yesterday and today, and most inspiring conversations with World Citizen Ken O’Keefe, who has declined US citizenship over US military dictatorship.

War Tax Resistance was front & center during O’Keefe’s two talks, as a means of asserting our “natural” rights and freedom from oppression. For me, the penalties are a secondary consideration – I am using the power of my dollars for peace, more importantly, i am acting loudly when the government engages in immoral and internationally acknowledged criminal acts of war.