Making your war tax resistance public brings attention to the harm caused by militarism and military spending, can help galvanize others to action against war, and encourages civil disobedience. However, many resisters, for whatever reason, choose not to be outspoken and public about their refusal to pay war taxes.

A few months ago, the war tax resistance e-mail discussion list took up this topic of public resistance when discussing how to deal with NWTRCC archival materials, including correspondence.

Several resisters expressed concern about a trend of people wanting to remain private about their resistance, associating relative quietness with an lack of willingness to take responsibility for their actions. Indeed, a hallmark of “civil disobedience” as a concept is choosing to be outspoken and public with one’s refusal to cooperate.

Some felt that resistance loses some of its value when undertaken in relative privacy. Others spoke out in support of those who choose to resist quietly, including Edward Hasbrouck, a long-time war tax resister and anti-draft activist and refuser. This was his response:

The draft resistance movement I was part of in the 1980s spent a lot of time arguing about (a) definitions of resistance and (b) whether quiet (closeted) nonregistration with Selective Service should be considered “resistance” or was “political”.

I don’t think either argument advanced our cause, or at least my cause. I’d rather recognize the diverse forms and self-definitions of resistance, and support all those who strive to resist war, than try to define a singular correct way to resist, or impose it on others.

I think the facts are pretty clear that there are hundreds of people who don’t like military conscription and violated the draft laws in some way than who publicized or told the government what they did.

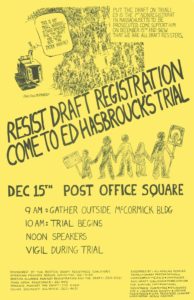

Click to see a collection of draft refusal posters, including this one, on Edward Hasbrouck’s website.

I chose to publicize and tell the government about my nonregistration, and was prosecuted for doing so, but that was a personal and tactical choice. I don’t think those who were closeted about their law-breaking were any less legitimate or less politically correct resisters.

Will Doherty, my queer comrade in public resistance and in support of closeted resistance, and my first teacher of the lessons for other movements of the movement for gay liberation, drew the analogy of the importance of gay people coming out of the closet. Coming out is an important part of the growth of a movement, which one can encourage in others by setting an example of coming out oneself, and supporting others who do. But one can’t impose that choice by outing others.

(I was out as bisexual to fellow inmates and guards in prison camp. I hadn’t really planned to talk about it, but it came up in a conversation, and word spread. I wasn’t sexually active in prison and both my fellow prisoners and the guards had seen my visits with a woman with whom I was obviously in love, which significantly affected how it was interpreted.)

As for tax resistance, I suspect that there are many more people who do things to reduce how much tax they pay, some of which including non-filing might be considered illegal by the government, because they oppose war, than who do so publicly or notify the government.

I welcome their actions, and encourage others to do likewise.

In any resistance movement there are those who take more direct and visible actions, and those (usually in larger numbers) who take similar actions more quietly, or don’t engage in them directly but provide various forms of support to those who do.

The best theoretical analysis I have seen of the relationship between closeted and public resistance comes from James C. Scott, the political anthropologist and scholar of peasant and other subaltern resistance:

“Much of the active political life of subordinate groups has been ignored because it takes place at a level we rarely recognize as political. To emphasize the enormity of what has been, by and large, disregarded, I want to distinguish between the open, declared forms of resistance, which attract most attention, and the disguised, low-profile undeclared resistance….

“For many of the least privileged minorities and marginalized poor, open political action will hardly capture the bulk of political action…. The luxury of relatively safe, open political opposition is rare… So long as we confine our conception of the political to activity that is openly declared we are driven to conclude that subordinate groups essentially lack a political life…. To do so is to miss the immense terrain that lies between quiescence and [open] revolt and that, for better or worse, is the political environment of subject classes….

“Each of the forms of disguised resistance… is the silent partner of a loud form of public resistance.”[Domination and the Arts of Resistance, Yale University Press, 1990, Chapter 7]

“Desertion is quite different from an open mutiny that directly challenges military commanders. It makes no public claims, it issues no manifestos, it is exit rather than voice. And yet, once the extent of desertion becomes known, it constrains the ambitions of commanders, who know they may not be able to count on their conscripts…. Quiet, anonymous,… lawbreaking and disobedience may well be the historically preferred mode of political action for… subaltern classes, for whom open defiance is too dangerous.” [Two Cheers for Anarchism, Princeton University Press, 2012, Chapter 1]

Both books are worth reading in their entirety, but seem to have been largely overlooked as contributions to the theory and practice of resistance to authority.

I quote these excerpts from Scott in an essay on the history of draft resistance since 1980 at: https://hasbrouck.org/draft/background.html

and in an essay on the politics of that resistance at: https://hasbrouck.org/draft/draft-identity-status.pdf

Peace,

Edward Hasbrouck

To see the entire conversation, check out this thread.

News coverage of Edward Hasbrouck’s draft registration resistance in 1983: https://www.upi.com/Archives/1983/01/15/No-jail-for-draft-resister/3641411454800/

Post by Erica Leigh

This is good advice! The journey of political action, like all journeys, begins with a single step. We should affirm everyone who takes a step. The militarists don’t want any kind of resistance. Ley’s give them every kind the ever imagined and a dozen more besides.

The use of the term “closeted“ is an interesting choice in the context of discussing civil disobedience. It implies there is something similar about being gay by birth and civilly disobedient by choice. I will have to think about that. But I do believe that a significant part of civil disobedience is accepting the consequences. I am not quite sure what to think about being quiet and thus potentially avoiding consequences. I am not an intellectual pacifist still have not thrashed out all these issues very well. I simply do what seems important and right to me and hope that others will do likewise for themselves. I am definitely the guy standing on the top of the hill yelling my disobedience. I realize from long experience that this is not possible for many people probably for many reasons. But I do try to tell people that being brave is not necessarily one of the requirements of being open and bold.