Review Lawrence Rosenwald

Autobiography of a Political Objector

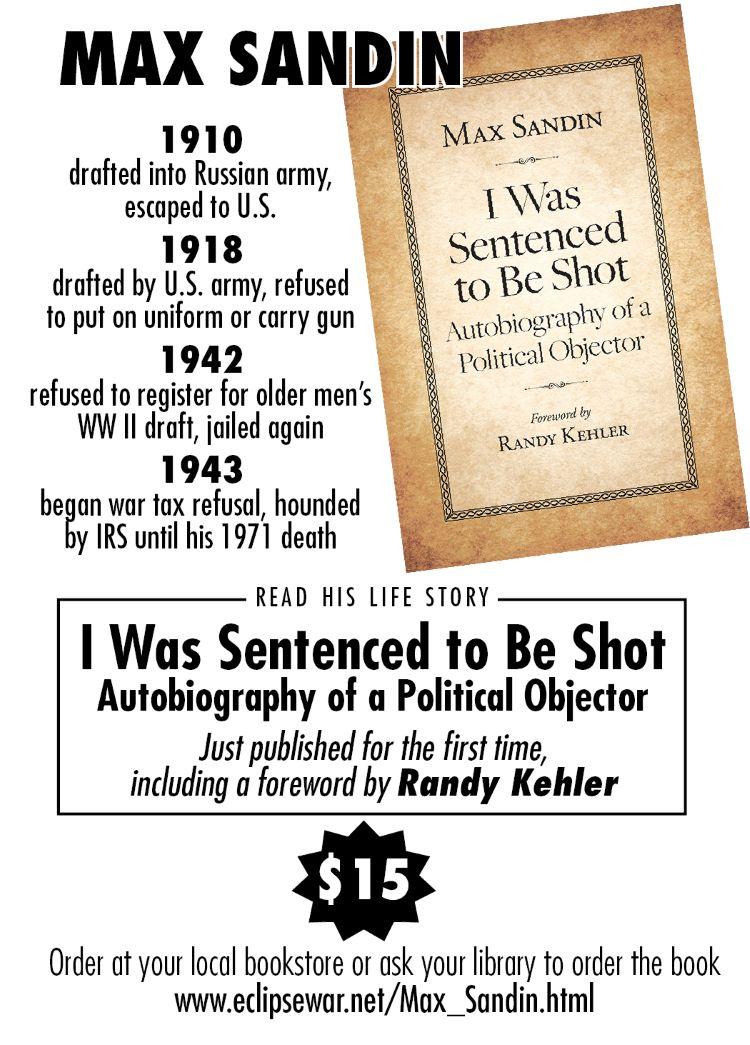

Max Sandim’s Memoir; Forward by Randy Kehler; Edited by Ed Hedemann & Ruth Benn ($15)

Published in May 2024

Max Sandin’s memoir begins with a story told by the late Randy Kehler, who met Sandin in 1963, in New York, on a bus taking them to the March on Washington. They talked the whole way. It was Kehler’s his first encounter with an ardent pacifist, and it made a big impact: “I often felt, consciously or unconsciously, that I was indeed, in my own way, following in – or at least trying to follow in – Max Sandin’s big footsteps in opposition to war and killing.”

We might read this encounter as a passing of the torch: the veteran pacifist hands pacifism on to the pacifist to be. Kehler then passes the torch to Daniel Ellsberg, and to all whom he inspired in his life and work. (As Bob Bady said at the memorial service for Kehler, “Randy sowed some seeds.”)

But the metaphor presumes that the torch itself, the pacifism itself, is unchanged. And that is not true. Though much in Sandin’s pacifism abides in Kehler’s, and in ours, much is transformed, something is lost, something is gained.

What abides? First the pacifism itself, fundamental and constant. For Sandin, I think for Kehler, for many of us, it is an intuition or revelation, not the result of reasoning. Then the willingness to see what pacifism implies: not just protests but draft resistance and war tax resistance. And the courage to live by pacifist principle. What Sandin and other World War I COs went through was appalling. They were tortured, there is no other word for it. (One of the book’s many virtues is its revelation of this history.) But few of them changed their views. They were pacifists, they were tortured, they were sentenced to death, they remained pacifists.

Max Sandin. Photo from publisher’s website.

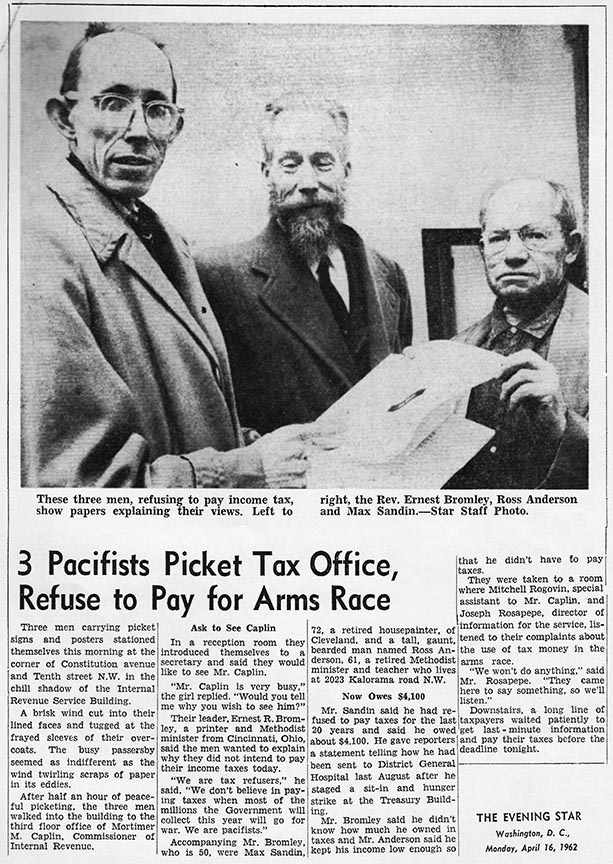

Kehler and others of his generation are in this tradition: a fundamental opposition to war, a conscientious sense of what that opposition entails, the courage to live in accord with what the conscience demands. Like Sandin, Kehler goes to jail for draft resistance, like Sandin he becomes a war tax resister. Sandin was stripped of his social security, Kehler was stripped of his house. Neither yielded.

Much abides, then. But much has changed too. Sandin was Jewish, for one thing. He translated his memoir into Yiddish. He was Jewishly literate and might have become a rabbi, as his parents wished. He was what many leftist Jews were in those days: socialist, communist, unionist, secularist. (He refused an offer from a Quaker meeting to pay his bail fee: “as an atheist I cannot accept help from a religious group” (165).)

I too am a Jew and a Yiddishist, and I sometimes feel the absence of the energies associated with these identities from the pacifist communities familiar to me. These energies are more combative, more unionist, funnier (though Sandin himself has no sense of humor), more cosmopolitan and polyglot, more irreverent than what I usually see. We have lost something in losing them.

But we have gained much too. A clearer sense of gender, for one thing. Sandin was stunningly indifferent to it. His marriage was amiable and long-lasting but patriarchal. He goes out to work, his wife takes care of the house and children, in particular their son Carl, diagnosed as “mentally retarded” (116); she spends four hours a day on street cars to get Carl to school and back. He is unmoved by the worries he is causing his wife and daughter. At one point he writes, unconscious of the irony, “because my family was upset about my stand, I decided to go west for a while” (155).

He is almost equally indifferent to questions of race. He makes occasional references to “Negroes,” he of course met Kehler on the way to the March on Washington, he met Wally and Juanita Nelson and Eroseanna Robinson, but he never wonders about what it was like to be an African American pacifist, cannot see racism as an American original sin, as pervasive and corrosive as the violence of war.

He is almost equally indifferent to questions of race. He makes occasional references to “Negroes,” he of course met Kehler on the way to the March on Washington, he met Wally and Juanita Nelson and Eroseanna Robinson, but he never wonders about what it was like to be an African American pacifist, cannot see racism as an American original sin, as pervasive and corrosive as the violence of war.

He was also strikingly un-Gandhian. He is not curious about his opponents, he does not regard them as conducting their own experiments with truth, he does not feel any bond of human sympathy with them. He is not like Gandhi, Barbara Deming, Bayard Rustin, Dorothy Day, Kehler. Our pacifism at its best is shaped by such figures, by their bridge-building curiosities and sympathies.

We have gone beyond Sandin’s pacifism; but his memoir is indispensable. It tells us where we come from, what we have retained, altered, lost, gained. All honor to Ruth Benn and Ed Hedemann for editing the manuscript so well, and may it find many readers.

Ed Hedemann (and Ruth Benn) always seems to be behind-the-scenes doing hard and hardly glorious work of writing and editing. Gathering information that becomes more valuable as time passes. Valuable because that information gives us a glimpse of the past in many cases which is important for those of us who may fall into the easy trap of thinking our struggle is hopeless. As some say, been there done that. Thanks to Ed and Ruth we can have some awareness of the long history of our struggle. It’s important history for us to know to support our current efforts.

Thanks Larry R, and Larry B too. In agreement with Larry R about Max’s home life, although I felt that in writing about his son Carl Max cared very much about his future. As I recall he and his wife were heartbroken to send him to an institution but they did bring him home for many weekends. Ed and I were both really sorry that when we got into working on this book we found out that Max’s daughter had died only the year before at 100. We just missed what might have been an insightful interview. Max’s absolutism would certainly have been a challenge for any spouse and family.

I would have liked to know more about how he felt about the prejudice against immigrants, which was especially strong in prison and courts against foreigners and probably Jews in particular — and then to be a conscientious objector too!

We were grateful to get the book done in time for Randy to see, but not in time for Randy to be sharing more of his sense of Max with us now.