We each come into this work in our own ways. The first war I was aware of was the amorphous Cold War. I did not know much about it other than it was between the U.S. and USSR. I was oblivious of nuclear weapons and the oblivion they could cause to the Earth. How we frame war and the stories we tell greatly impact people’s ability to relate to the stories.

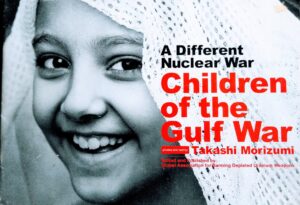

Book published by Global Association for Banning Depleted Uranium Weapons

I was reminded that with the 30th anniversary of the U.S. bombing of Iraq recently. The anniversary did not register for me at the time of the bombing. I was still in elementary school and my exposure to the war was having a classmate’s sister who was in the Army visit our school as if for show and tell equipped with MREs; later we would be assigned soldier pen pals. I was unaware that there were people throughout the world expressing their opposition to the war following in a long tradition of conscientious objection. It would be the next intensified bombing campaign of that war with Operation Desert Fox in December of 1998 that I would meet these life long committed pacifists.

I was inspired by the stories of the people of Iraq shared by a member of the Catholic Worker who had traveled to Iraq that was followed by an action in the White House calling for the end of the bombing and economic sanctions. It was as if a whole new way of life opened up and I moved into the community that largely hospitality to veterans—some of whom struggled with mental health and substance use issues. As I was wrapping up my formal studies my awareness of war in its multitude of forms and wide ranging effects expanded.

Roots Action Vieques Flyer

The line between conventional and nuclear weapons began to blur when the U.S. began using guided bombs and missiles containing depleted uranium (DU)—a waste product from nuclear reactors—in Iraq in 1991. An article, How the U.S. Made Dropping Radioactive Bombs Routine states: “Within one or two years, grotesque birth defects spiraled—such as babies with two heads. Or missing eyes, hands and legs. Or stomachs and brains inside out.” Soon the U.S. began expanding not only the weapons from DU to undepleted and slightly enriched uranium weapons, but also the scope of countries in which these weapons were used: Kosovo, Afghanistan and Vieques in Puerto Rico. The navy had begun bombing the U.S. territory in 1941 and had dumped so many contaminants on the island that they were unable to detect the origins of the island inhabitants’ sickness. One resident stated, “People aren’t hearing the bombing everyday but the consequences are felt.”

That statement could be said of any of the places that the U.S. has engaged in military operations or the close to 900 military bases the world over as well as within the U.S. The testing of nuclear bombs continues to poison the original inhabitants of this land. From 1944 until 1986, 30 million tons of uranium ore was extracted on Navajo lands. At present, there are more than 520 abandoned uranium mines, which for the Diné represents both their nuclear past as well as their radioactive present in the form of elevated levels of radiation in nearby homes and water sources.

Sole of a Shoe on the Highway of Death in Iraq. Photo by Christiaan Biggs from Wikimedia Commons.

There has been growing concern in the Diné and other indigenous communities not only of the loss of the lives of revered elders, but also their role as holders of traditional knowledge. The people of Japan shared similar concerns and have created a 3-year denshona program to be the official memory keeper of a Hibakusha to learn and keep their tale of atomic nuclear bomb survival alive.

The amorphous war that was in the background of my upbringing of nuclear weapons and the bombings of Iraq came together when visiting the al-Amiriyah nuclear bomb shelter in Baghdad prior to the Shock and Awe campaign. Our delegation visited the site where women and children would gather at night to sleep, eat, and watch TV, but on the night of February 13, 1991 took the lives of over 400 people. I was chilled to my bones upon seeing what had once been a living, breathing, laughing, crying human incinerated by the heat of the “smart bomb” upon the wall. It was reminiscent of the images of Hiroshima.

Amiriyah-Shelter photo by Shane Claiborne

I am grateful that the only strategic arms control agreement, the New Start, has been renewed. I imagine that many of you were involved in nuclear disarmament over the years and maybe it was that issue that furthered your commitment to refuse to pay for the mechanisms of war. Or it may have been one of many other issues of U.S. warmaking at home and abroad. It seems important to recall what inspired us to go against this nationalistic religion of warmaking as we claim and share our stories. I would love to hear your story of what got you involved in war resistance and refusing to pay for it and how you are still working on decolonization. Maybe you would be willing to share your story for tax day this year?

Post by Chrissy Kirchhoefer

When I was in college I was faced with the possibility that I might be drafted to go to Vietnam. I ended up having a deferment so I was not drafted. But I had decided that if I was drafted I would not go. I had not had to decide what I was going to do instead. When I graduated from college I began working in human services and realize that meeting human needs was a much lower priority of the US government then supporting the military. I decided I was not going to pay federal taxes to support the military. If I was not going to fight in a war if I was drafted, it seemed clear to me that I should not pay for someone else to fight in a war.

Larry, Thanks for sharing some of your story here and more in-depth on Facebook. I am having greater appreciation of the impact of the Vietnam War on so many at such an early stage of adulthood; how that direct contact with war has influenced so many WTR and the NWTRCC network.

Thanks for sharing your story, Chrissy. I grew up with the Cold War, but the beginning of my consciousness was really during the Vietnam Way – I was debating the topic of US Unilateral Military Intervention in 10th grade and started to see some of the issues and truths of war and govt policy, but I still was not clear about my own personal part in the war. I opposed the Vietnam War, but still registered for the draft when I turned 18 in 1972, still being young and foolish. By 1974 I had a much clearer vision of myself as a pacifist and war resister. But it was only when I returned from my years as a Peace Corps volunteer in Africa that I became very clear that contributing to the war with my body or my taxes was wrong, wrong, wrong.

Wow that is a powerful story! It is hard to imagine having enough life experience at 18 to be determining matters of life and death with all of the pressure put on young men especially in those years with the draft. I am appreciative of your resistance and sharing your evolution with your life experiences.